I've talked before about being a "Plotter". I don't write without knowing everything that's going to happen in the story (but leaving room for surprises to happen along the way). So what does that look like? Well, for me, in many ways it's like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. First, you have to decide what difficulty level you're going for, what length of project. Is it a 200-piece puzzle, or a 550-piece? Then: is it the picture of puppies, the sailboat, or the bridge of the Enterprise? After that is the hardest part: starting. You see, it's not just a puzzle. It's a puzzle that has been knocked over. Because you don't have any of the pieces to begin with. Here and there on the floor you can see a couple of puzzle pieces, but on their own you have no idea what they are or how they fit into the bigger picture. But following the trail of pieces leads you to more, and eventually you find the mother lode: the stash of all the puzzle pieces somewhere underneath the coach. Of course, the work isn't over yet. Oh no. You have to sort through the pieces, find which goes where - tossing out any pieces that you think belong to another puzzle altogether. It's hard work, this, but satisfying. You get to see the picture come together. And it's a fascinating experience, at times, to find that what you thought was a bird's eye is actually a black shirt button, and that edge piece is really an odd-shaped center-piece. But once the picture is complete, you can start the actual writing, knowing in full what you're going for, what the actual story is. Because if a character isn't heading for a specific destination, they really aren't headed anywhere at all. Right now, in planning Book 3 of The Sleepwar Saga, I'm at the early piece-collecting stage. I have a handful of disparate segments, but I'm just on the verge of them leading me to the main pile of spilled pieces. And soon will begin the main planning of the book. And then, the writing. I just can't write about the basket of puppies without seeing what the completed jigsaw puzzle looks like in the first place - writing about a few loose puzzle pieces just leaves me with a mess of purposeless prose.

0 Comments

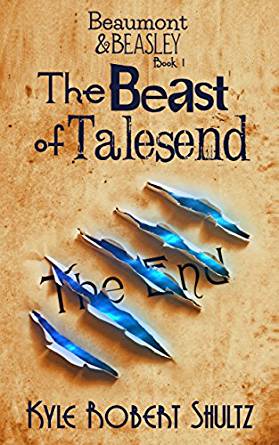

Could also be called: Sky Captain and the Temple of Doom. I love a good pulp novel - and a good pulp movie serial as well. Here I get something of both. For while this book is a tribute to the old pulp works, to me it reads more as a pastiche of the cinematic pulp adventures than the written ones. Indeed, the author seems to say as much in the book itself. Furthermore, I catch more than a hint of the modern tributes to the pulp classics. For example, it feels more like Sky Captain than it does Sky Raiders. More The Rocketeer than The King of the Rocket-Men. And that's not a bad thing. A modern sensibility to the period-pastiche is a nice touch which I appreciate. And while it does a good job emulating a 1930s environment (I was able to picture the whole thing in black and white) I personally think it has elements of a more contemporary storytelling style that help it remain relevant to today's reader. It's not too deep, I'll tell you that. Nor is it trying to be. What this book wants (and what it succeeds at) is to be a rollicking adventure drenched in the spirit of 1930s pulp sensibilities. It is pretty steadily-paced with a plethora of cliffhangers, and it never flags. Some storytelling problems include very uneven chapter lengths (which disrupt the pacey flow a tad) and a very swift ending which follows a late plot revelation that could have fueled much more story beyond that point. In addition (and this is the only thing that knocks the rating down a peg) there are frequent (and I mean ubiquitous) typos and punctuation errors. If these bug you too much (and they usually do for me) then prepare yourself because they are impossible to ignore. A lot of word repetition finds its way in as well, though this is a stylistic criticism rather than a technical one. I don't want to seem down on this work as I enjoyed it a lot (and look forward to reading the sequels which this initial book leaves room to improve upon) but the flaws have to be noted. And they do detract - even if less than they might have. "The Skyhook Pirates" is intentionally derivative. Don't expect much innovation here. The skill involved here was stitching together various elements to achieve a surprisingly cohesive whole. It ought not to be as good as it is with so many disparate ideas masquerading as one story, but it works dammit. The diversity helps make the plot seem fresh as the story unfolds - like each new chapter of the movie serial has its own character, but is telling one overarching story. So, yeah. Get it if you like old pulp stories. Avoid it if you don't, because it makes no pretense to be anything other than what it is - and rightfully so. Very entertaining.  Hello. My name is Doug, and I am an addict. It's been four days since my last adverb. Already I find my fingers itchy, desperate to type that beautiful "-ly" at the end of of a word. Adverbs are not inherently bad; I know this. Used in moderation they are descriptive and poetic. But I know I can never use just one. Sure, it starts with a "softly" or a "wryly". But before you know it the adverbs are spilling off of the screen and I wake up in a pile of my own vomit, staring at the page I have written in my stupor: "Hi there," said Fred breezily. "Hello," Jennifer replied flatly. Frowning, Fred delicately inquired, "Is everything okay?" She sighed. "I guess," Jennifer answered despondently. Friends don't let friends abuse adverbs. I need your help. It's a struggle, but if I can get through today without an adverb, I know maybe I can do the same again tomorrow. And then the next day. And the next. One sentence at a time, my friends. One sentence at a time...  You shouldn't choose because, of course, "Plotter" is the obviously correct selection. I kid, but let me back up a bit: What are these terms? Writers tend to use these words to describe the two basic types that make up their group. "Plotters" plan the story out in advance, and write to an outline. "Pantsers" make it all up on the fly. So which is better? This is what I came here to explain: there is no choice. You don't decide which path to follow; you learn which group you are already in. It's not about technique, it's about the way you naturally write. Some will say that Plotters leave no room for inspiration to hit, or that Pantsers hit writer's block and give up too easily. Neither of these are necessarily (or even often) true. Let me lay my cards on the table: I'm a Plotter. And how. I can't even start writing until I have every last beat of the story figured out. I just can't do it. (Or rather, I can't do it well, which is kind of the point.) If I try to write without a very sophisticated outline, the story just veers off into nowhere and I have to delete vast swathes of text and start again. For me, a story needs to have a shape. I don't just put finger to keyboard and see what comes out. I know what comes out: nonsense. A story is about progression, about characters following their nature but encountering hiccups and overcoming them and developing in certain precise and entertaining ways. If you just let them bumble about doing whatever they feel like, it might be believable but it sure as hell won't be entertaining. Ah, you may well cry, that is what rewriting is for. And this is true. Many writers find the story in the redraft stage and get everything into shape then. Me? I'd rather do all that pesky rewriting before the writing has actually started. It's much easier to redraft a "beat sheet", or treatment, than a 90,000 word document. But have I abandoned all artistic integrity by sticking to an outline? Have I hamstrung myself, leaving out all sense of inspiration and become a slave to a blueprint that I have bound myself to? Not at all. In those cases where things start developing in ways that contradict my outline (and yet seem potentially more interesting than my outline) I see where that takes me and develop a new outline where necessary. (Or else realize I was right the first time and return to an earlier file which I conveniently saved when I began to deviate.) Similarly, Pantsers are not necessarily more prone to giving up due to writer's block than Plotters. We Plotters have the same writer's block - we just experience it earlier (in the planning stages). Pantsers, in some ways, have a better reason to just plow ahead and see where the story takes them; if a plotter becomes stuck on how to implement his or her outline then it becomes harder to just power through the blockage. So neither is necessarily beneficial. There is no reason to choose between the two, based on merit. What is important is to find out which of the two you are and do so quickly. The more time you waste following the wrong technique, the harder it will be to write anything half-way decent. I legitimately do not understand Pantsers. How is it possible to craft a comprehensible and entertaining story without knowing where everything is leading? There are so many strands to a novel that I do not see how a writer can cause them to artistically convene and converge in any kind of believable and satisfying manner by doing it on the fly. And yet it is done. Again and again, every single day, by artists whose talent is far above my own. I couldn't do it, that is for sure. It's not about choosing, it's about discovering. And I discovered very early in my life that I can only produce a satisfactory story by doing all the donkey work up front. You may be the opposite. You may find that any outlining you do results in a mundane and predictable story that satisfies no-one, and the only way to create something of worth is to sit at the keyboard and figure it all out as you go. It's not a choice; it's an identity.  Beaumont & Beasley, Book 1 Some people will call this a "Beauty & the Beast" retelling, which it definitely isn't. (Indeed, that tale is specifically referenced as a story within the text.) Instead, it's a wonderful fantasy adventure that uses elements and iconography from that classic fairytale (among others) to tell a fun and whimsical new adventure. Like one of my favorite TV miniseries (The Tenth Kingdom) this first in a new series of books is set in the fairytale kingdoms many years after the famous events. Except in this case, thousands of years have passed, causing the tales to become legends many no longer believe in. One such skeptic is Nick Beasley: a so-called "magical detective" who makes it his business to debunk instances of supposed supernatural occurrences. And he barely gets paid for his efforts. "The Beast of Talesend" describes what happens when Beasley gets caught up in events that prove to him the existence of magic without any room for doubt, and places him firmly in the role of sorting out some of these mystical dangers. While the inciting "twist" comes later than might perhaps be optimal to set up the real story, and is easily guessable by most, I shan't spoil it here for fear of upsetting those who might not have anticipated it. Suffice to say that a certain occurrence forces Beasley to become part of this magical world despite his natural lack of desire. What makes this book so entertaining is not simply the "updated fairytale" nature of it (which we've seen before - if not specifically in this form) but rather the pace, the wit, and the loveable characters. The setting itself is vaguely described - being a sort of "timeless modern" in nature - in a part of the Afterlands transparently modeled after the United Kingdom (with Wales being habitually overlooked again) that clearly expects us to imagine something classic and yet contemporary at the same time. This follows through to the tone, where Beasley's dry acerbic nature clashes with Cordelia's Jane Austeny plucky-yet-occasionally-proper adventurous spirit. The dialogue and the first-person narration are easy to read without feeling as though the text has been too modernized for our ears. The plot is fairly basic, and the villain archetypal rather than layered, but this is all in the service of setting up a fairytale-based world and Beaumont and Beasley's place in it, while moving through a rollicking adventure quest. Might I have preferred a more complex story worthy of telling in itself? Perhaps (though future installments may yet provide such a creature) but for a book intended to set up a world, a tone, and designed to emphasize the roles and functions of a specific set of characters, it does its job pretty much exactly right. And yet because of this book's (deliberately) shallow nature and slight story, I find myself unable to give it the full five stars some might imagine it deserves. Being something of a stingy mark-giver, I reserve five stars (usually!) for the most exceptional writings, or those that affect me the most deeply. "The Beast of Talesend" is not striving for such a target, so to not achieve it is a success rather than a failure, in a way. Four stars without reservation, then, for something so entertaining and breezy to read. Looking forward to more from these characters!  Diversity is important. Now, I don't believe in tokenism, but I do believe in representation. As a straight white male, it is all too easy for me to be blind to the way my 'type' is over-represented in fiction. That most fiction seems to be directly catered to me, to appeal to me, to feature me. But having diversity among your characters is not only about representation; it's also just good drama. What your characters look like might not seem superficially important (in text there is no color) but even if all of the characters are white (or black, or Hispanic, or desi) it is important to make each distinct. Basically, the less variation in the characters' cultural and developmental backgrounds, the less inherent drama there is in their interactions. Why limit yourself? No matter how well you define your individual characters, if they all share so many of the same characteristics then there is much less scope for clashes. For me, as a function of where I live, it is easy for me to create a naturally diverse cast. I simply look at my friends and co-workers and draw from them - as they are from various backgrounds and ethnicities, so will my own characters be. I especially think about the teenagers I work with, since the Sleepwar Saga leads are all teens as well. As I look to real young people I know from which I can extrapolate brand new fictional versions, I naturally will create a diverse group as that is the culture that surrounds me. Were I still living in some of the more overwhelmingly white areas I have lived in before, perhaps I would have to work that much harder to ensure I created a realistically and entertainingly diverse cast of characters. That's not to say I always succeed in my efforts. Only after the fact did I realize that all six of my leads (and the supporting cast of "Straw Soldiers" as well) are cisgendered hetereosexual able-bodied people. Clearly this is an area I will need to deliberately focus on if I want to be representative (and to mine all resources for inherent drama). Actually, one of the characters in "Straw Soldiers" is gay, but as it never came up in the text no one will ever know. What about gender? More than half of the world's population is female, so why are so few fictional characters female? Especially in movies and on TV, but books can be just as guilty. I want to be diverse. I want to be representative. Not just to ensure that straight white men are not the only (or even primary) type that gets stories written for them, but because when drama is all about the way characters clash and interact, why would any writer remove potential for this by limiting the variation among the core cast? But while sometimes this comes easily, at other times I realize how far I still have to go if I want to meet my goals. It's so easy to surround yourself with people like yourself - to write about people like yourself - that you just don't notice how insufficient this representation actually is.  And why write it? This is just a question I was thinking about lately, and figured I'd jot down some thoughts. You see, 'genre' is an interesting concept which so many people seem to get wrong. Genre doesn't define content; content defines genre. In other words, no good 'Young Adult' book (since that's the category I'm discussing today) began with the author thinking: "I'd like to write a YA novel. What elements do I need to put in to make it YA?" Many writers do, indeed, think like that. But not the good ones. Writing YA isn't about taking some of the staples of the genre (dystopian future, strong female protagonist, vampires) and figuring out a plot you can build around them. This only leads to inferior fiction. No, instead 'Young Adult' fiction is merely fiction that is about being a young adult. It's about writing your story in such a way that it is defined by the experience of being a teen (or person of similar age). Not about featuring teenagers; rather, it is about being a teenager. The entire subjective experience should be the way an actual young person views and chooses in the world. This is what makes a YA story, not the plot elements. So why write YA? Why is the young adult experience such a popular topic for authors and readers alike? My guess is that the experience of 'coming of age', of being right at the point in one's life where one is transitioning from dependency to autonomy, is simply the most inherently dramatically rich period to form a story around. This is a time when emotions are at their height, when the weight of the future first begins to burden a young mind, when the person they will be for the duration of their lives begins to fully take form. Obviously, this makes for a vast well of story potential to be mined. And adults - who are actually the main consumers of YA fiction - will connect with the material every bit as powerfully as those who are going through the same experience depicted in the story. We have all been that age, and any story that properly conjures up the reality of having been that age will bring us older folks back to when we felt the exact same way. One of my favorite movies is Where the Wild Things Are. It is based on a young children's book, and is about the experience of being a young child. But is not for young children. Oh, there is nothing there that is unsuitable for kids. I just don't think it caters to them particularly. It doesn't speak to them in any strong way, because its purpose is to remind us who have left that period behind of exactly what it felt like to be a kid. What we went through, the way the world treated us. It reminds us of that time, and helps us relate to those who are currently children. Kids don't need that. They're already living it. It's the rest of us that sometimes need to be reminded of just what a fearsome and difficult time childhood actually is (or can be). That's what I like about YA, and why I choose to write it. It is, in a basic way, about being at a time in our lives that defined us, that we struggled through, that we sometimes find it all too easy to forget. And sometimes it has vampires in it. |

J Douglas BurtonAuthor of "The Sleepwar Saga" YA fantasy series. Also Victorian pulp SF series "The Star Travels of Dr. Jeremiah Fothering-Smythe". Archives

August 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed